|

|

Introduction

Make no mistake, going to sea in a small boat can be dangerous and this is certainly compounded if the skipper either missed, forgot or didnít fully understand the weather forecast.

We are bombarded by accurate weather forecasting these days. I hope you are not jeering at that last statement because the forecast on the TV always seems to be wrong! I quite agree. It is not exactly wrong. Normally the weather that is forecast is correct, but it does not arrive exactly on time.

Letís have a think about where we can get hold of weather forecasts.

Look outside often and note clouds, wind direction, temperature, and if you

have a barometer, the air-pressure. Any quick fall or rise means lots more

wind!

TV - The BBC give very good land forecasts and even give us a glimpse of a synoptic chart for a few seconds! Iím afraid some of the other TV forecasts are not much more use to the sailor than telling us it will be light all day until it gets dark, then dark all night until it gets light again! If you have teletext, you can see the shipping and Inshore waters forecast.

Newspapers - Most give a land area forecast and some give out the shipping forecast. Most have a synoptic chart, which also helps.

Radio - Most local radio stations, if they cover towns near the sea give out good nautical weather regularly. The times and frequencies of these are noted in Almanacs.

BBC

radio 4 broadcast the "Shipping forecast" issued by the Met

office, four times per day. These are also noted in Almanacs. The Coastal

Station reports are broadcast twice per day.

BBC

radio 4 broadcast the "Shipping forecast" issued by the Met

office, four times per day. These are also noted in Almanacs. The Coastal

Station reports are broadcast twice per day.

Telephone - There are various telephone weather forecasts available by fax and recorded

voice. These little cards are given away free in Yachting mags, and stations

etc. See an Inshore waters Met fax?

The inshore forecast is incredibly detailed for a small area. Also available

are good

3 - 5 day planning forecasts

VHF Radio. In the UK the Coast Guard gives out weather information every four hours

and more frequently if there are strong wind or gale warnings in

operation. This will the shipping forecast, then the inshore forecast and an

outlook for the next three days.

Again broadcast times for UK and Europe are carried in Almanacs.

The Internet is becoming a widely used weather information device.

There are many web sites offering up to date weather information. Have a look

at www.digital-reality.co.uk Its

great! Inshore forecasts, shipping forecast, synoptic charts. Just about

everything you need!

Harbour offices and Marinas always have an up to date forecast for their area posted on notice boards. This is usually in the form of the latest Shipping Forecast and Local Inshore Waters Forecast.

We have no excuse for not knowing what the weather has in store for us on a

coastal passage.

BBC Shipping forecasts

On Radio 4 on 198 KHz Long wave. Be careful here as the frequencies for LW and MW are very close together. It is all too easy to miss the forecast because you are listening to the wrong Radio 4 broadcast.

The shipping forecast is broadcast at time of writing at the following times. NB, recently these times have been changing so check up in the "Radio Times"

0048 , 0535 , 1200 local time and 1755 local time. Local time means the clock time, which is different at various times of the year.

The forecast is in four parts.

- The first is any "Gale Warnings".

- Next comes the "General Synopsis".

This tells us where the weather systems are and where they are likely to be going.

- Next are the "Sea Area Forecasts" for the next 24 hours.

For each area or group of areas, we hear the wind direction and strength and any changes. See Using the "Beaufort scale" The precipitation (rain, hail, snow etc) and then the visibility.

- Next are the "Coastal Station Reports" These are now only broadcast at 0048 and 0535. This is unfortunate.

They tell us exactly what weather is happening at various points around the British Isles. We hear first the wind direction and strength, precipitation, visibility, pressure, then pressure change. With experience, this allows us to decide where fronts have passed by or are just about to hit. Very useful.

|

| CRUCIAL STUFF! |

|

There are quite a few weather terms used in all the forecasts and with out some knowledge of them they make little sense. When you hear the shipping forecast, the terms used sound rather vague. In fact, each term has a specific meaning Ė the following sections will help you interpret.

This refers to the speed at which the low or high pressure system, currently affecting our weather, is moving.

- Slowly: Up to l5kn.

- Steadily: 15-25kn.

- Rather quickly: 25-35kn.

- Rapidly: 35-45kn

The speed at which the atmospheric pressure is changing is a measure of how close together those isobars are on a synoptic chart. The closer together they are, the windier it will be, as air tries to escape from high to low pressure. Therefore, the faster the pressure is changing, the windier it will be.

SEA STATE

wave heights

Smooth - 0.2m - 0.5m Slight 0.5m - 1.25m Moderate 1.25

- 2.5m Rough 2.5m - 4m

Very rough 4m - 6m. High is bigger than that!

Means that, within a sea area, the wind may well come from all directions. This is not to say that the Met Office does not know from which direction the wind will blow. It merely means that the sea area is too big to give one wind forecast for the whole area.

Usually a low pressure system is passing directly over the area.

Are not part of the forecast, but they are a crucial term. They show areas of the same air pressure, like contour lines on a map denote the same height. The closer they are to each other, the more wind there will be. Not only that, but you can work out roughly how much wind there will be in particular area by using the shown on page 5 of your practice nav tables. Geostrophic scales

This is a term describing a change in the wind direction anti-clockwise. If

the wind is blowing from the Southwest and it "backs" into the West it

will blow from South, Southeast, East, Northeast, North, Northwest and finally

West. (Backing the clock)

Means the opposite. The wind would change in a clockwise direction, straight from Southwest to

West.

FRONTS

FRONTS

Warm front

- the leading edge of the warm air sectorCold front

- the leading edge of the cold air sectorOcclusion -

forms when the cold front overruns the warm frontEarlier I mentioned using the "Geostrophic scales" and you can use them again to find out the speed in Knots of a warm, cold or occluded front. Be careful here to use the correct scale. To do this, measure across the front between the isobars. Then pop your dividers onto the scale (at the correct latitude) to find out the speed of a front. Measuring accross the isobars like this also allows you to find out the rough wind speed in that area. Knowledge of the speed that a front is travelling is very important. As you read on you will see that weather and wind are directly affected by fronts.

Writing down a whole shipping forecast is something of an art. I used to be

able to do it, but then I bought a programmable tape recorder that tapes the

whole lot without waking me up at 0048 or 0535. Very useful! I suggest

everyone gets one! At around 20 quid, itís money well spent.

Itís all very well writing it all down, but what does it mean in practice? Letís have a look at first principles.

Where does our weather come from?

The UK has a temperate climate, mainly warm and wet. Thatís why we have the most beautiful country in the world!

The reason for this is that most of the air moving across us comes from the Atlantic Ocean.

"Tropical Maritime" air is warm and wet. Good wholesome British rain is in this lot!

Some of the other air masses we receive are:

- "Polar maritime", (cold and wet) winds from this sector can bring snow.

- "Polar continental" (cold and dry) very cold and some snow.

- "Tropical Continental" (warm and dry) dusty and thunder storms.

I want to deal mainly with Tropical maritime weather.

A series of Temperate Low Pressure Systems constantly sweep their way across the UK bringing wind, rain and poor visibility with them.

These are born out in Mid Atlantic when two different air masses meet; warm, wet Atlantic High Pressure and cold, wet Arctic High Pressure. It is difficult to think of air having trouble mixing, after all thereís nothing there, is there?

The next time you are on an aircraft and it flies through some turbulence, you are experiencing the effects of different air meeting. It does not mix easily and a lot of energy is produced. Thunder and Lightning are caused by it.

Anyway, these "Lows" form, grow

quickly and head for us! ( Due to the Earth spinning.) They also rotate

"anti-clockwise" (in the Northern Hemisphere). They are about as

big as Europe by the time they arrive.

Highs give us settled weather in the main.

Air rotates clockwise around a high pressure centre and blows outwards towards the low pressure. So with a high sitting over the UK we would expect Easterly winds in the English Channel.

These winds are generally light in nature, but can be moderate to fresh around the Dover Strait, due to the funnelling effect experienced there.

In the summer when we have a high over us, the weather is sunny and warm and there is not much breeze. Often though, the visibility is not as good as you may think because of high pressure haze; usually about 3 to 5 miles.

Interaction between highs and lows

This is very important. The proximity of highs to lows governs the strength of the wind and its general direction. The closer they are together and the wider the difference in pressure, (gradient) the more wind. If for example we have a large high of 1040 mb's over central France and a Low over the centre of UK, there will be westerly gales in the English channel. Or a high over the UK and a low over the Baltic will give strong Northerly winds in the North sea.

| Fronts

Within the Low there are the two air masses and at the joints between these, there is usually trouble in the form of "fronts". |

|

THE COLD FRONT

The warm, wet air is slow moving and the cold, drier air moves much faster. The whole lot is spinning and therefore the Cold Front is always catching up with the Warm Front. I like to think of the Cold Front as the bulldozer of a frontal system, forcing the warm wet air forward and upward before it and eventually overtaking it. By the time the Low reaches the UK, the Cold Front has normally caught up with the Warm Front around the middle of the low and formed an occlusion.

Because the warm, wet air is being forced up quickly, it loses temperature and the water within condenses into rain with very large droplets. This falls as heavy showers around the Cold Front. Sometimes this rain is forced up by rising warm air, to great altitude where it freezes. This can happen many times and result in hail. Cold air falling next to warm air rising creates a lot of friction and this we hear and see as thunder and lightning

I have drawn the fronts as lines. In fact they are a chaos of mixing air which may cover many miles.

is completely different. It is not driving, it is being driven. Air is

compressible and the violent push from the Cold Front is not felt as such at the

other side of the warm air sector. The warm, wet air is gently coaxed up and

over the cold air in front. This process is gradual and therefore the onset of

rain here is also slower. First there is light rain and drizzle, which

gives way to heavy and prolonged drizzly rain within the warm air

sector and shortly before it. At some indeterminate point through the Warm Sector, this heavy rain

becomes more isolated. This is a time to be careful.

The rain stops, the vis starts to clear and we start to relax. watch out

because the Cold Front will then make itself felt and give heavy showers. After the

passage of the two fronts, the showers will slowly die out.

As the name suggests, these are a mixture of both warm and cold fronts. You

may get any of the features of either fronts. As the cold front is travelling

faster than the warm, so both fronts occlude.

This happens quicker the nearer you are to the centre of the depression. Typically

these occlusions are the sign that the low is filling and dying out. However a

new low may well form at the point where the two fronts split. This is usually

to the South East of the old parent low. This new or secondary low can be much

more vigorous.

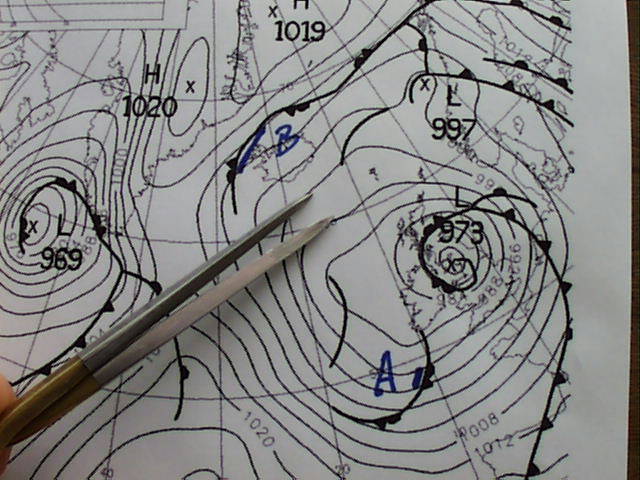

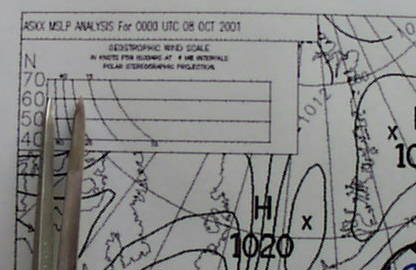

Geostrophic scales

Use your dividers to measure the distance between two isobars, (be careful of

damaging your screen) then using the scale at the correct latitude, find out what

Beaufort force is likely at that time.

On the south coast it was pretty breezy that day! You can obtain a rough

speed of a front in a similar way. By measuring between isobars at the front.

Occlusion "A" was three hundred miles from Plymouth and travelling at

40knots. This was an 0600 synoptic and the front arrived at 1300. Right on

time!

Occlusion "B" is travelling much slower. About half the speed as it

takes much longer to cross between isobars. With the correct scales, you can also measure the speed of warm cold and

occluded fronts. This is

particularly useful, as then you can work out roughly how long before they hits or

clear your area!

You must be careful here though, as the frontal weather will arrive before the

synoptic feature. for example, rain fall starts well before a warm front

arrives.

Synoptic charts are normally issued at 0000UT, 0600, 1200, and 1800UT.

It is very important to understand that they are pictures only of those times.

If it is 1000UT when you look at the 0600UT chart, then things will have

changed! Use the methods above to decide where fronts are in real time.

| Clouds

There are various cloud types associated with a frontal system. If we watch one approach and pass over us, this is the sequence of cloud types we would expect to see. |

|

| The first cloud signs of an approaching Warm Front are "Cirrus" and "Cirro stratus", sometimes referred to as "maresí tails"; wisps of very high cloud in a blue sky. |  |

| You may see a mackerel sky instead. "Mackerel Skies and Maresí tails make tall ships carry small sails" |  |

| Later the sky becomes greyed out by "Alto Stratus".

Mid height cloud. The sun can still be made out through this cloud, but as a white fuzzy ball. Soon after, we get light rain |

|

| Next comes the heavy rain cloud called Nimbo Stratus.

Low cloud. No definition in the sky, (flat-bottomed cloud) and heavy drizzle! We are now in the Warm Sector and can expect this weather for some time. |

|

| Eventually we will start to see a little definition in the sky as more Cumulo cloud starts to develop due to the fast rising air on the Cold Front. Then there is a period with both flat and fluffy, grey cloud. A mixture of Stratus and Cumulus cloud: - Stratocumulus. At this point we might just glimpse a sunray again.

|

|

| As the Cold Front approaches, this will give way to Cumulo

Nimbus cloud. This cloud looks rather like the billowing white

clouds of steam coming from a power station chimney, but itís grey and

huge, with sunbeams coming through.

My favourite weather! But very violent. |

|

| After all that lot you might even get one of these! A

Rainbow after a Cold Front shower. Exercise 21c |

|

It doesnít really matter how much rain we get, apart from the fact that we canít see much through it, but the wind direction and strength is crucial to the sailor.

It makes the sea " a bit bumpy, Daddy" according to Toby, my son, then three years old. We were rounding the Lizard in some huge seas. He was a master of understatement even then!

The wind changes direction at various stages as the fronts pass.

Wind follows Isobar tracks, but in a Low-pressure system it also blows in

to the centre, trying to fill up the low pressure from the higher pressure

around the low, a bit like an inverted Katherine wheel firework. Wind blows

anticlockwise around low pressure and clockwise around high pressure in the

northern hemisphere.

Buys Ballots law says "Stand with your back to the wind and the low

centre is on your left" in the northern hemisphere.

The wind will "Back" (Compare wind arrow A to wind arrow B)

It will also increase steadily.

The wind will "Veer". (Arrow C)

You will have strong winds, but they are usually steady in direction

The wind will be very squally (gusty).

This is the windiest part of the system.

During the passage of the Cold Front, cold air is descending at great speed. It hits the sea surface and can fan out in all directions. You can have half a dozen different shifts in wind direction in a few minutes in this area, and some very strong gusts. REEF before it!

Often the sailor is caught out by the Cold Front because he sees the weather improving. The sky gets brighter, it stops raining and becomes showery. Then bang, he is laid over by a huge squall!

The wind will veer (Arrow D) and eventually decrease.

All these things do happen, but as I have said before, this area is chaotic and cannot be timed exactly.

We cannot see the wind so how do we know how much there is?

There are two ways to gauge it.

Becoming very common these days are on-board Anemometers, which can measure the wind strength in knots, metres per second, miles per hour or the "Beaufort wind scale" These machines are very useful but are prone to electrical failure and erroneous readings.

There is a better method, which always tells the truth.

The Beaufort Wind Scale is a way of telling the wind speed by looking at the sea state.

How far you can see at sea is very important.

I canít tell you how frightening it is with less than a mile visibility, when you have come back over the Channel and are faced with finding the right bit of England. Your EP is pretty ropy by this point, having not seen anything since France, it will have a circle of error of up to ten miles. If you could only see five miles! As it is you might be headed straight for the rocks!

During the passage of the Low, the visibility changes dramatically.

Before the Front we have "good" visibility, but as the Warm Front approaches, it will reduce to "poor", since the warm, wet air is full of moisture.

On the front we may even get fog (I will cover fog as a separate subject) Certainly the visibility will stay poor throughout the Warm Sector.

It will improve again as soon as we start to be overtaken by the colder drier air of the Cold Front, where the visibility can be very good indeed. Twenty five to thirty miles is not uncommon.

However, it will reduce to poor in the heavy showers.

Exercise 21d

A nightmare at sea. We cannot see where we are, where we are going or who is going to run us down!

There are two main reasons why fog forms. Radiation fog (land fog) and Advection fog (sea fog)

This occurs mainly in September and October, when the days are getting shorter, but the weather is still good. We get hot sunny days with clear skies, but as soon as the sun starts to sink, we all run for a sweater. It gets cold very quickly.

During days like these, the land heats up and water evaporates into the air.

There are clear skies, so the heat of the day can radiate off into the atmosphere during the evening. The evaporated water vapour then condenses and fog forms. This cold, fog filled air then rolls down from the hills into the river valleys and out into the estuaries where it affects us. We also get heavy dew.

The good thing about radiation fog is that as soon as the air is reheated, the fog will burn off and disappear. The sea is relatively warm at this time of the year, having been heated all summer, so as the fog floats out to sea, the air warms up again and the fog disperses.

When fog sits in an estuary on the ebb tide, it will often disperse as the new flood comes in, again because this water is warmer.

Advection Fog

This is formed when warm, moist air comes into contact with a colder area. This is rather like the result of breathing onto a window, when your warm, moist breath condenses on the cold window pane.

This can happen at sea around our coast for two reasons.

I have already said that you can get fog on a Warm Front. This is because the warm, moist air of the Warm Sector is being pushed against the colder air of the Cold Sector.

We also get Advection fog particularly in the spring, when the water of the

English Channel and the North Sea are as cold as they ever get. If there is a

SSW airflow from the Atlantic, carrying warm, moist air up from the Azores, this

air runs over our cold water and we will get fog. This fog can be very thick and

widespread and will only clear when there is a change in the wind direction,

e.g. if the wind changes to a Northwesterly. The northwest wind is colder and drier and

there is not such a temperature difference between sea and wind.

In the summer, when the land warms quickly, air rises on the land and cold air from the sea is drawn in to fill the gap.

This is a sea breeze and usually starts to blow about 11am until the land starts to cool again in the evening. When the land cools, air falls and blows back out to sea. Ė a land breeze.

These winds are very useful to the pleasure sailor because he tends to want to go sailing on sunny days in the summer. The trouble is thatís when there isnít much wind! Land and sea breezes are not strong winds. They are usually up to about Force 3. The sea breeze is felt first very close to shore, (within a mile). Then, as the day progresses, it can be felt further off shore, typically about four miles off, but it can be much further.

I hope you now know where to get the weather and how important it is not to miss the forecast!

- You know a few weather terms, to be able to understand what youíre listening to.

- You should also have a good idea of where the UK gets its beautiful weather from and what happens as a low pressure area passes over us, in terms of wind rain and visibility.

- Look up and you can gain a lot of information by watching the clouds.

- Remember to keep checking that barometer!

- Fog is a tricky one. Just like on the roads, itís best to delay setting off on passage until it clears.

After all that lot, you deserve some nice weather and a sea breeze!